The findings come from a map put together by Check Point Research and genetic malware analysis firm Intezer, making it the first-ever comprehensive analysis of state-backed Russian-attributed threat groups that have been found to engage in disruptive cyber warfare. “The size of the resource investment and the way the Russians are organizing themselves in silos makes them able to carry out a multi-tiered cyberespionage offensive,” Check Point researcher Itay Cohen told TNW. It’s worth noting that all of Russia’s cutting-edge cyberespionage operations, including the 2016 US elections hack and the devastating Petya ransomware attacks on Ukraine in 2017, have been attributed to three intelligence services — the FSB (Federal Security Service), the SVR (Foreign Intelligence Service), and GRU (Main Intelligence Directorate for Russia’s military) — none of which directly collaborate with one another. By collecting, classifying and analyzing approximately 2,000 Russian APT malware samples, the cybersecurity company found 22,000 connections between the specimens that shared 3.85 million pieces of code. The samples fall into 60 families and 200 different modules, per the analysis.

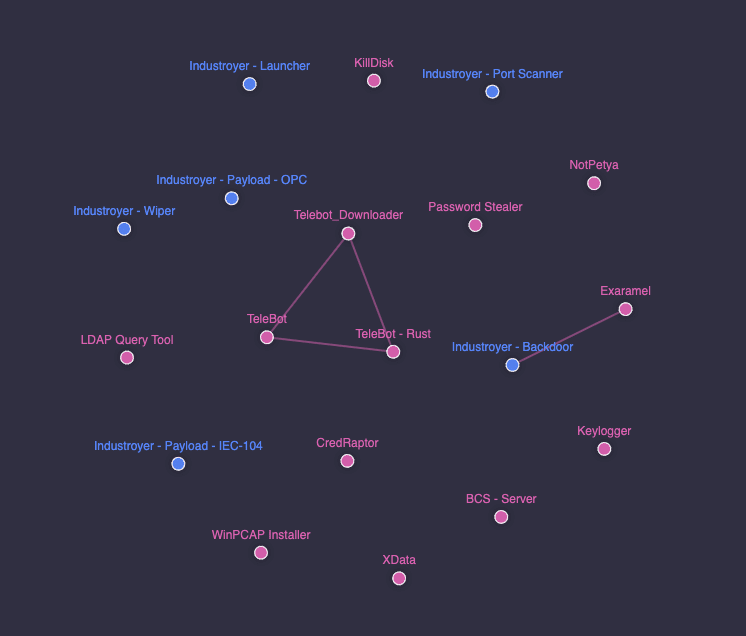

A visual taxonomy of all Russian malware

“While each actor does reuse its code in different operations and between different malware families, there is no single tool, library or framework that is shared between different actors,” the researchers said. The research adds to growing evidence of Russia’s ongoing efforts to step up its operational security by avoiding reuse of same tools across different advanced persistent threat (APT) groups, thereby overcoming a critical risk that “one compromised operation will expose other active operations.” The result is a resilient, well-oiled cyberattack machine with a staggering investment in money and resources to develop malware tools and libraries, the researchers hypothesized, underscoring the sprawling scale of the country’s snooping and sabotage operations. “The biggest challenge problem we had was that there is no naming standardization for malware and threat actors in the infosec industry,” Cohen said. “We had to step carefully between different articles and research papers and draw the lines.” To identify connections between different Russian APTs and the associated malware families, the researchers worked by dissecting each sample into pieces of binary code — called genes — each of which were referenced against malicious and legitimate software in which the code was previously observed. Subsequently, the connections based on references to open-source libraries were filtered out, yielding a cluster of interconnected nodes that visualize the “mutuality” between samples belonging to different actors.

No cross-actor connections

The research is surprising for what it didn’t reveal. While there were thousands of inter-family connections (a piece of code shared between different samples of the same malware family) and cross-family connections (code shared between samples from different families but originating from the same actor), no cross-actor connections were found. The approach is suggestive of extraordinary levels of investment in operational security, indicating that several Russian hacking groups are simultaneously building entire malware toolkits from scratch despite the obvious overlap. More notable, the connections among clusters showed that code (such as functions) and encryption schemes were shared between different teams and projects of the same actor:

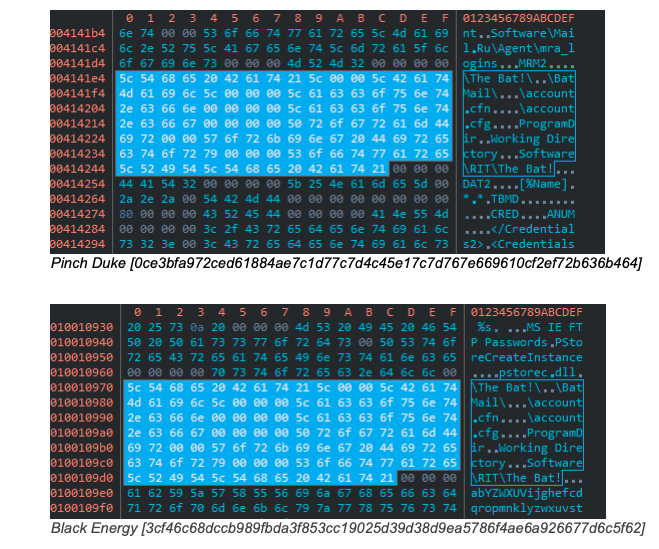

Both PinchDuke and BlackEnergy share credential dumping implementation for Outlook and the Moldovan email client The Bat!. BlackEnergy and Energetic Bear (aka Dragonfly) had an exact match in their self-delete functions. Potao and Sofacy (or Fancy Bear) X-Agent have similar implementation of the executable malware loader. Telebots’ Exaramel shares similar backdoor code with that of Industroyer’s, suggesting Exaramel is a newer version of the backdoor.

Potao malware, in particular, was used for targeted espionage campaigns directed at Ukrainian government, military entities, and news agencies in 2014-15. It was also used to spy on members of MMM, a Ponzi scheme popular in Russia and Ukraine. What’s more, links between Exaramel and Industroyer have been suspected before, but this is the first time it’s been conclusively proven with code-based evidence. If anything, the approach is no less different from that of the US. The cache of NSA-developed Windows hacking tools that was used to target banks and leaked online by the Shadow Brokers in 2017 was unlike the CIA Vault 7 malware released by Wikileaks. When asked about the possibility of threat actors covering up their tracks by obfuscating code similarities, Cohen said: “It is possible, but unlikely. Even now some of the code in these samples is obfuscated. Moreover, in addition to static-matching, the samples are also compared when are they loaded to memory, hence overcoming anti-static analysis techniques such as obfuscation.” Although the benefits of sharing existing code results in a reduction of human effort, the fact that “Russia is willing to invest an enormous amount of money and manpower to write similar code again and again … indicates that operational security has a priceless meaning for the Russian actors,” the researchers concluded.