Peter was diagnosed with motor neurone disease (MND), the same incurable illness that killed Stephen Hawking. The disease degenerates the nerve cells that enable us to move, speak, breathe, and swallow. In time, it can render a person physically paralyzed while their brain remains alert, locked into a body it can no longer control. Peter was given two years to live. But Peter had a plan to beat the prognosis. He was going to become a cyborg. Peter had a headstart in his race against the illness. He had the first PhD granted by a robotics faculty in the UK, a bachelor’s degree in computing science, and a post-graduate diploma in AI. He’d also written a book titled The Robotics Revolution. He used this experience to develop a vision for what he calls “Peter 2.0,” a cyborg who would “not just stay alive, but also thrive.” He’d escape starvation by piping nutrients into his stomach, and avoid suffocation by breathing through a tube. His paralyzed face would be replaced by an avatar, and his disabled body would be wrapped in an exoskeleton standing atop a self-driving vehicle. He also needed a new voice.

Computing communication

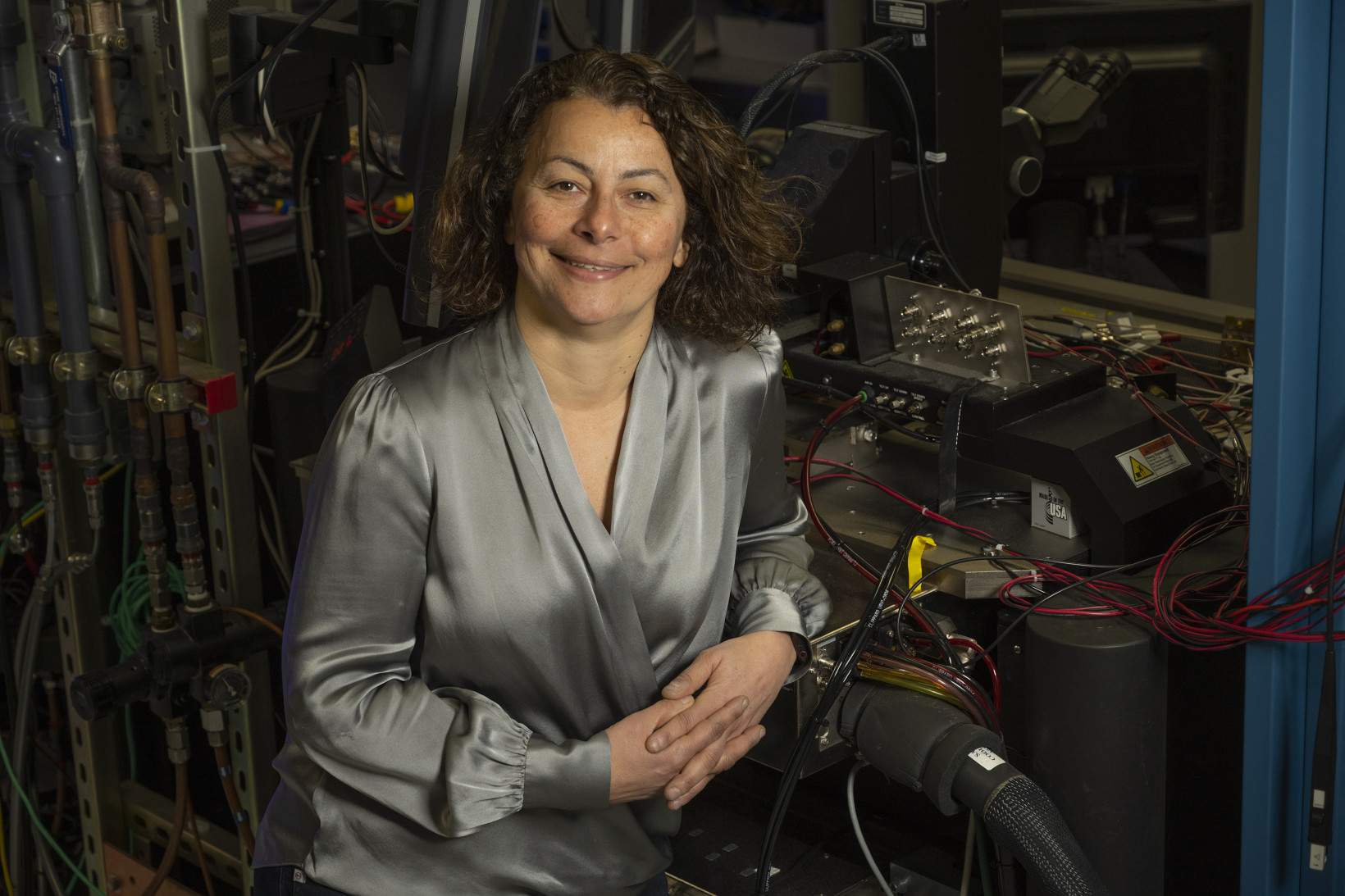

In early 2019, Peter gave a speech at a conference in London. Among the listeners was Lama Nachman, the head of Intel’s Anticipatory Computing Lab. Lama had her own experience with MND. Her team had upgraded the communication system that powered Stephen Hawking’s iconic computerized voice. For Hawking, Intel attached an infra-red sensor to his glasses that detected movements from his cheek, which he used to select characters on a computer. Over time, the system learned from Hawking’s diction to predict the next words he’d want to use in a sentence. As a result, Hawking only had to type under 20% of all the characters he needed to talk. This helped him double his speech rate and dramatically improve his ability to perform everyday tasks, such as browsing the web or opening documents. Intel named the software the Assistive Context-Aware Toolbox (ACAT). The company later released it to the public as open-source code, so developers could add new features to the system. But Lama initially didn’t want to adapt ACAT to Peter’s needs. Peter could already use gaze-tracking technology to write and control computers with his eyes. Developing a new one seemed like a waste of Intel’s resources. “But then we realized the original premise of ACAT, which was essentially an open system for innovation, was exactly what was needed,” Lama told TNW. Her team decided to use ACAT to connect all the pieces of Peter’s cyborg vision: the gaze-tracking, synthetic voice, animated avatar, and autonomous vehicle. “We shifted to do two threads: one was research on the responsive generation system, and the other one was essentially taking ACAT and adding gaze control support.” But Peter still needed a new voice.

Finding a voice

Hawking had famously chosen to keep his synthetic voice. “I keep it because I have not heard a voice I like better and because I have identified with it,” he said in 2006. But Peter wanted to replicate the sound of his biological speech. Dr Matthew Aylett, a world-renowned expert on speech synthesis, thought he could help. He recorded Peter saying thousands of words, which he would use to create a replica voice. Peter would then use his eye movements to control an avatar that spoke in his own voice. Aylett had limited time to work. Peter would soon need a laryngectomy that would allow him to breathe through a tube emerging above his chest. But the operation would mean he could never speak again. Three months before Peter was due to have surgery, the clone was ready. Aylett gave Peter a demo of it singing a song: “Pure Imagination” from the 1971 film Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory. Peter’s operation would take place in the month in which he’d originally been told he was likely to die. The night before his operation, Peter tweeted a goodbye message alongside a photo with his husband.

— Dr Peter B Scott-Morgan (@DrScottMorgan) October 9, 2019 The operation was a success. But Peter would remain mute until his communication system was ready. By this point, the exoskeleton and autonomous vehicle had been shelved, but the electronic voice and avatar were still part of the plan. The system soon arrived. It came with a keyboard he’d control by looking at an interface, and an avatar synchronized with his speech. Peter 2.0 was ready to go.

Upgrading the cyborg

There was another big difference between Peter and Hawking’s visions for their systems. While Hawking wanted to retain control over the AI, Peter was more concerned about the speed of communication. Ideally, Peter would choose exactly what the system said. But the more control the AI is given, the more it can help. “A lot of the time, we think when we give people the control, it’s up to them what they do, said Lama. “But if they’re limited in what they can do, you’re really not giving them the control.” However, ceding control to the AI could come at a big human cost: it risks sacrificing a degree of Peter’s agency. “Over time, the system starts to move in a certain direction, because you’re reinforcing that behavior over and over and over again.” One solution is training the AI to understand what Peter desires at any given moment. Ultimately, it could take temporary control when Peter wants to speed up a conversation, without making a permanent change to how it operates. Lama aims to strike that delicate balance in the next addition to Peter’s transformation: an AI that analyzes his conversations and suggests responses based on his personality. The system could make Peter even more of a cyborg — which is exactly what he wants. Peter: The Human Cyborg, a documentary chronicling his transformation, airs on the UK’s Channel 4 on August 26. So you like our media brand Neural? You should join our Neural event track at TNW2020, where you’ll hear how artificial intelligence is transforming industries and businesses.