Death Stranding, the long-awaited first game from Hideo Kojima after his split from Konami, is on its way. And with each new trailer, we see that Stranding will include the same crazy bullshit we’ve come to expect from a Kojima production: a script heavy with exposition, on-the-nose names and titles ripped straight from a twelve-year-old’s first sci-fi story, and a heavy dose of the supernatural. If nothing else, it looks to be a typical Hideo Kojima game. But these trailers also provide a timely reminder that Death Stranding will face heavy scrutiny upon its release. Included in the release date reveal trailer is a scene in which a presumed antagonist licks Léa Seydoux’s face. Compared to what Kojima usually puts his women through, this is somewhat tame. However, it is a reminder of his long history of uncomfortable depictions of women in his narratives — his reliance on tired sexist tropes and an unapologetic implementation of women as visual rewards for his perceived male player base. And given Death Stranding’s stark resemblance to The Phantom Pain, there is a justified concern that it will be more of the same.

Gender disparity in context

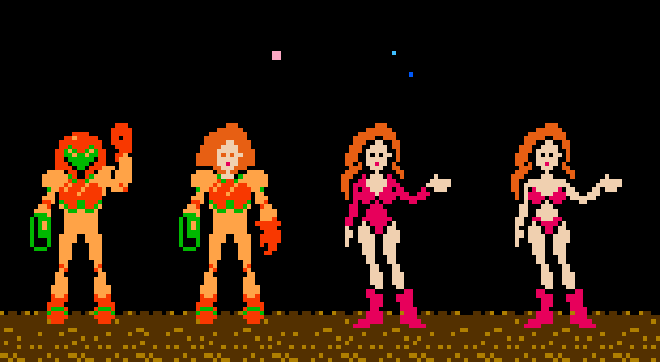

The gaming landscape has always skewed male. In recent years, the number of women and men playing games has leveled out, but it is still the case that the development side of gaming is overwhelmingly male — the most recent investigation into gender in gaming revealed that 88 percent of game developers are men. Female-led games still suffer from being undermined and under-marketed, while women in the industry will tell you that Gamergate did not happen in a vacuum and was rather the most visible example of the systematic abuse that women are subjected to in the industry. In the late 1980s, the damsel-in-distress adventure was the typical gaming formula. The two most popular games of the time, Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda relied heavily on the trope — and continue to do so — and the majority of releases throughout the life-cycles of the NES and SNES depended on a male hero with a woman at the end of his journey. So the revelation that Samus Aran, the protagonist of Metroid, was a woman had the potential to be groundbreaking. That one of the coolest characters in gaming — and what child of the ‘80s, fresh off Star Wars, thought space bounty hunters weren’t cool? — was female represented an incredible marketing tool to open up an industry almost exclusively marketed at boys to girls and women. Yet, Samus was never supposed to be female. All the marketing and even the instruction booklet refer to Samus as he and him, and the reveal that Samus is a woman wasn’t made with representation and demographics in mind. Rather, it was conceived as a reward for its male players. While completing the game in five hours sees Samus remove her helmet and thus reveals her identity, this powerful moment is undermined by anyone who finishes in three hours which sees her don a skin-tight leotard like something out of GLOW. Finishing the game in one hour reveals the same image, except Samus is now decked in a bikini. This use of Samus in revealing costume as a reward for finishing the game continued in Metroid II and Super Metroid, all the way up to Super Smash Bros. for the Wii U, which had director Masahiro Sakurai declaring, “And here’s Samus in shorts!” The almost exclusive representation of women as sexual trophies has become foundational in gaming. Kojima’s ever-intensifying treatment of women as sexual objects and prizes, be it Meryl, Eva, or Quiet, is a continuation of the tired and restrictive tropes present in those early days of the games industry. And while Japan has been slower than most to move away from traditional gender biases (in 2019, represents an embarrassingly feudal attitude to the roles of men and women in society), this does not excuse creators — whether they’re Japanese or not — for maintaining these tropes, whether it’s Kojima decking a character in a bikini or Shigeru Miyamoto hijacking an entire game to convert it into a furry damsel-in-distress nightmare. Japanese companies may not face the same backlash for sexist tropes that western companies now do, but that does not make their reliance on exploitative tropes less unsettling, and sets a worrying precedent for the treatment of women in a context where they face continued harassment and violence both within and outside the gaming industry.

Tentative steps forward

Jill Valentine, the protagonist of Capcom’s Resident Evil, is arguably one of the first meaningful female player-characters in gaming. Easily on par with her male colleagues, she is not defined by her clothing but rather by her skillset. The recent Resident Evil 2 remake has continued this trend with Claire Redfield, who is narratively better-equipped (both physically and mentally) to deal with the infestation of Raccoon City than her male counterpart. It is a major fillip in such a long-running series that so many of its female characters are demarcated by what they do and not what they wear.

Women as rewards

This concept of using women as a reward is not confined to video games. Throughout media, a dangerous precedent is maintained which sees women depicted as attainable objects rather than genuine characters. Masamitsu Hidaka, show-runner of the Pokémon anime, had this to say on the high turnaround of female characters in the series: “It gives boys some new eye-candy every once in a while… girls are more customizable and you can change their outfits, like when they are in bathing suits.” This in itself is a troubling sentiment, but when you consider that he is referring to characters whose ages range between ten and thirteen it becomes downright creepy. And while the intent may be for ten to thirteen-year-olds to watch the series, it is important to remember that the creators behind these sexually-driven characters, controlling their behavior and clothing, are adult men. Every single example of women being used as a rewards system for male players — whether it’s Mario receiving a kiss on the cheek or sex in return for rescue in The Witcher 2 — communicates the idea that women are fundamentally there for male amusement. And as more women populate the roles of player, developer, and journalist these games perpetuate the attitudes that make the industry a consistently dangerous place for women to be.

Kojima’s women

Hideo Kojima has played a prominent role in this broader story. His continuing and, frankly, intensifying use of women as objects has colored the Metal Gear Solid series as a hub of sexist tropes; permeated with women in prominent roles being designed with male titillation in mind, culminating in the blatant and unapologetic sexualization of Quiet in Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain. As early as Metal Gear Solid, and its GameCube remake Twin Snakes, the principal female character is used for little more than male players’ enjoyment. Early in the game, Snake can snoop from a ceiling vent at Meryl Silverberg exercising in her underwear. Later, while Snake is looking for a disguised Meryl among the faceless guards littering the game, the clue to her identity is the exaggerated way she wiggles her hips as she walks. And once you find her, she’ll run to the bathroom, where enterprising creeps can catch her in the middle of changing if they’re fast enough. Much like the characters of Resident Evil, Meryl is capable and, for the most part, appropriately dressed. But these moments of forced nudity, meant only as a reward for creepy players, completely undermine that identity. It would be easy to dismiss this as a product of the times — the original Metal Gear Solid was released in 1998 — but to do so would be irresponsible. As Anita Sarkeesian related in her Women as Reward video, these aren’t “accidents or glitches, they’re intentionally put into the game by the designers and, as a result, indicate the value that the designers, themselves, place on these female characters.” Kojima’s defenders might rely on the argument that his games hark back to ‘80s action movies and these tropes are simply a part of that, but that fails to lay accountability where it belongs and empowers developers like Kojima to do it all again. Which he did in Metal Gear Solid 3, in which Eva — in a demonstration of Kojima’s often incomprehensible writing — is a triple agent who has infiltrated antagonist Volgin’s organization (ostensibly by sleeping with him) but is also in contact with you and the Chinese, all while doing flips on a motorbike and — you know what? It’s best not to try and understand what’s going on in Metal Gear Solid 3. All of this is achieved while wearing a flight suit unzipped to her waist, showing off her cleavage — a view the game encourages you to take in with its R1 zoom feature. This is later compounded when guiding an injured Eva out of the game’s signature jungle. Do so unscathed and you’re rewarded with Eva in her underwear. In Metal Gear Solid 4, Kojima continues his use of interactive cutscenes which allow you to tactically zoom in on cleavage, jiggle a character’s breasts by shaking your controller, and look up a character’s skirt when she picks up a cigarette Snake dropped totally by accident. Move on to Peace Walker and the same mechanic provides a view up sixteen-year-old Paz’s skirt. Then, in a game that does not utilize fully-rendered cutscenes, Paz gets the only one and she just happens to be in her underwear throughout. Which all leads to 2015’s Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain. There’s no nudity as reward here; you don’t have to do anything for it — you don’t have to complete the game, or a series of challenges, or anything. Quiet is just there in a bikini, for no reason. Metal Gear Solid’s writing has always been, at best, ham-fisted. It’s ridiculous, over-the-top, and often, frankly, bad. That The End and Quiet share the same characteristic but differing states of undress isn’t inconsistent writing, however. Rather, it’s that The End — a man — is a character, while Quiet is an object; a trophy to adorn your screen. Kojima was unfazed by the criticism invoked by Quiet’s portrayal. Before revealing her photosynthetic nature, he stated that when we found out the real reason behind her costume we would be “ashamed of our words and deeds” — and, of course, we weren’t. In reality, Quiet is a culmination of Kojima’s attitude towards women and as technology has improved and games have looked steadily more photo-realistic, Kojima’s women have become steadily more naked. In Quiet, he has created what he likely wanted to all along: a silent mannequin for men’s enjoyment — you can even paint her if you want. Sadder still is that, in the sprawling marathon of The Phantom Pain, Quiet is one of the few genuinely interesting characters. This is mostly down to Stefanie Joosten’s motion-capture work, as well as being exempt from delivering any of Kojima’s lines. But those positives mean nothing when undermined, like Samus and so many others, by the men behind her creation.

What good looks like

With all that in mind, it begs the question: what exactly does good representation look like? While the moral implications against which we might measure Kojima’s use of women — and how it reflects an overall trend within the industry — may be plain, it is important to consider a tangible metric also. They may be hard to find, but there are examples of positive portrayals of women out there. Among the most prominent in recent years are the women of Naughty Dog games. Under the supervision of Amy Hennig, the Uncharted series has included an impressive roster of female characters throughout. It has also demonstrated how increasing criticism of the industry’s attitude towards women has helped effect a change, with Neil Druckmann citing Feminist Frequency as a catalyst for the decision to include more women as the series goes on. The apogee of Naughty Dog’s dedication to positively representing women is probably Ellie from The Last of Us. Under Kojima’s direction, Ellie likely would have become a useless McGuffin — à la Resident Evil 4’s Ashley Graham — but The Last of Us presents her as a typical teenage girl in an intensely atypical world. So immediately obvious was Ellie’s importance to a slowly changing gaming landscape that Druckmann made a conscious effort to buck industry conventions and bring her to the foreground of the game’s marketing. This, in an industry that has been entrenched in the idea that women can’t sell games for decades. Arguably one of the greatest female characters in gaming is Aloy from 2017’s Horizon Zero Dawn. From the moment you take your first tentative steps into Guerilla Games’ sprawling antique dystopia, the game is supremely female. Be it the protagonist or the matriarchal society she finds herself in — even the Nora’s god is female. As Aloy’s world expands, the maternal society may fade but we are still presented with a significantly more egalitarian society than many we have seen before. In Aloy herself, we observe the epitome of what female characters can rise to with the right attitudes behind them. She is emotionally intelligent, respected for her discretion and technological prowess rather than her looks, and persistently dressed in practical clothing that reflects the styles of both male and female garments throughout the game. But she is also feminine without it compromising her character. Aloy is a remarkably human character, equally capable of empathy and tearing the circuitry from a mechanical behemoth. But it is Aloy’s narrative, as well as her character, that marks her as unique within the landscape of AAA games. Growing up having never known her parents, Aloy embarks on a journey to not only save the world, but to discover more about herself. Where other games might shape that gap in her development as male, Aloy’s focus is instead on finding a mother figure as her journey of self-discovery takes centre-stage. Said mother figure is the brilliant Elizabet Sobeck, who, in a continuation of the female themes, had saved humanity centuries before after a male colleague had all-but-doomed it to total annihilation. Even the conduit for that salvation is female-presenting. The final, satisfying payoff of Aloy’s discovery narrative is that while she resolves the questions surrounding her lineage, she also follows almost exactly in her mother’s footsteps. It is a bold narrative beautifully told, and if, in just these two characters, you notice a trend, you’ll see it’s really as simple as presenting female characters as human beings, rather than the warped ideals of straight men. Aloy and Ellie feel like original characterizations simply by virtue of being deeply human within a landscape that otherwise paints women as objects. And when we consider them against a character like The Quiet, for instance, we see just how far Kojima has gone to strip her of all humanity in order to create something for male players to gawk at.

Convincing the critics

Hideo Kojima’s fans are aggressive in their defense of him. In researching this piece, it was difficult to access the original reactions to Quiet’s character model as Google had been hijacked by male fans and their weak think-pieces, Reddit rants, and message board meltdowns excusing Kojima’s depiction of women. He is a genius, they reason, and therefore he can do what he wants. They even go so far as to suggest that Kojima’s women are examples of positive representation because they’re tough, “badass”, and shoot guns just like men. And all this discourse, weak though it may be, highlights an important issue of agency and, in particular, choice. Much of the defense of offensive and exploitative portrayals of women is that these female characters have, in some way, chosen their attire and behavior. This basic misunderstanding of where agency lies within gaming — and art — is at the heart of why so many men defend creators like Hideo Kojima. It also spotlights a starting point for the lessons that games need to start teaching to help men unlearn the privilege that has been reinforced for them since birth: that agency lies with the creator and not the creation. Unsurprisingly, these lessons are most effectively taught by women. One need only look at games like Journey and Portal or even outside gaming to media such as Netflix’s She-ra, Sex Education, and Russian Doll or Black Panther, Wonder Women, and Captain Marvel to recognize that including women — and aiming for wider diversity — both in development and intended audience results in better writing, better characters, and better content. By attempting to cut women out of the picture, we’re dooming ourselves to the same boring tropes and depriving ourselves of genuinely original content. It remains to be seen how Kojima has handled the women of Death Stranding, especially given the shift we are starting to see in the landscape that has already produced some of gaming’s best female characters. With such a long history of dehumanizing women and exploiting them as prizes for his male gamers, it doesn’t look like he’s going to be part of the solution. In recent years, we have been privy to so many examples of anger — and even violence — directed at women in and around the gaming industry. In this context, efforts to maintain the status quo, in which women are trophies whose existence depends solely on male pleasure and reward, risks reinforcing the underlying attitudes that contribute to this behavior. The inclusion of women in the industry, and the development of well-rounded female characters, has been shown to lead to innovative and original games. And all of this highlights just how far behind the times Hideo Kojima has fallen — the claims that he’s harking back to the 80s suddenly feel more pertinent. And while we may laud Kojima’s contributions, we also owe it to ourselves (and the medium we love) to question and discuss the ways in which major developers contribute to the culture surrounding women in video games.